|

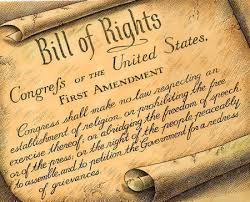

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees basic rights or freedoms to the people of the United States. They are the freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to peaceably assemble, and the right to petition the Government. In recent months Public Health Departments, in conjuction with state and local officials, have among other measures, placed restrictions on public gatherings and religious gatherings. Doesn’t that violate our constitutionally guaranteed rights? The short answer is, not always. Let’s take a look. There are many cases winding their way through the courts, challenging governors in various states who have put restrictions in place to stop the spread of COVID-19. Most of the cases challenge restrictions placed on houses of worship in violation of the First Amendment’s freedom of religion clause. The other significant group of cases challenge restrictions limiting peaceful protests and other gatherings, in violation of the First Amendment’s right to peaceably assemble. In order to determine the constitutionality of pandemic restrictions placed by the various states, we have to turn to the Supreme Court. The first coronavirus related case to be ruled on by the Supreme Court was South Bay United Pentecostal Church V. Newson, No. 19A1044 (May 29, 2020). The church had filed a lawsuit against California Governor Gavin Newsom after he put in place an Executive Order limiting attendance at places of worship to 25% of building capacity or a maximum of 100 attendees. The church claimed that this violated their First Amendment rights. The Supreme Court rejected the church’s claim, and upheld Governor Newsom’s right to place restrictions on in-person religious services in an attempt to control the spread of the coronavirus. But how can that be? It is a clear case of government restricting the free exercise of religion. Here’s what Chief Justice Roberts had to say in his majority opinion: “The Governor of California’s Executive Order aims to limit the spread of COVID-19, a novel severe acute respiratory illness that has killed thousands of people in California and more than 100,000 nationwide. At this time, there is no known cure, no effective treatment, and no vaccine. Because people may be infected but asymptomatic, they may unwittingly infect others. The Order places temporary numerical restrictions on public gatherings to address this extraordinary health crisis”. The opinion further states that “…those restrictions appear consistent with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Similar or more severe restrictions apply to comparable secular gatherings, including lectures, concerts, movie showings, spectator sports, and theatrical performances, where large groups of people gather in close proximity for extended periods of time”. The California order was neutral regarding its treatment of all in-door gatherings, religious and secular, and therefore lawful. For a full reading of the Supreme Court opinion go to: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/19a1044_pok0.pdf . This case has wider implications over the debate regarding coronavirus restrictions. According to the Roberts’ opinion, “Our Constitution principally entrusts the safety and health of the people to the politically accountable officials of the States to guard and protect.” Roberts is citing here a precedent established by Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, 38 (1905). This case upheld the authority of states to enforce compulsory vaccination laws because the regulation in question was “necessary in order to protect the public health and secure the public safety”. The decision further explained that individual liberty is not absolute and is subject to the police power of the state. “There are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good. On any other basis organized society could not exist with safety to its members. Society based on the rule that each one is a law unto himself would soon be confronted with disorder and anarchy”: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/usrep/usrep197/usrep197011/usrep197011.pdf . Roberts opinion continues: “When those officials undertake to act in areas fraught with medical and scientific uncertainties, their latitude must be especially broad. Where those broad limits are not exceeded, they should not be subject to second-guessing by an unelected federal judiciary which lacks the background, competence, and expertise to assess public health and is not accountable to the people.” The bottom line is, the courts are going to defer to elected officials in the states to determine how best to protect the health and safety of its citizens during the pandemic. According to Christopher Dunn of the New York Civil Liberties Union, Jacobson V. Massachusetts will be the case that frames all litigation around coronavirus-based restrictions on public gatherings. What happens when the government starts rolling out a coronavirus vaccine later this year or next year? Can the government force me to take it? In a word, yes. Jacobson v. Massachusetts specifically states that “It is within the police power of a State to enact a compulsory vaccination law, and it is for the legislature, and not for the courts, to determine….”. There are specific exemptions to vaccination laws which I will address in a future blog post.

The Supreme Court has also rejected lawsuits from churches in Illinois and Nevada looking to strike down coronavirus restrictions. Does this mean that all lawsuits challenging coronavirus restrictions are doomed to fail? Not necessarily. The restrictions have to be applied without preference to content or viewpoint. For example, if officials restrict in-door religious gatherings to 50 people, they must restrict all in-door gatherings to 50 people. It would be unconstitutional to allow a 100 person “Black Lives Matter” protest to take place and not a 100-person protest against coronavirus lockdowns. New York ran afoul of the content neutral requirement when it put into place bans on non-essential gatherings of individuals of any size for any reason, and then modified it. The modification allowed for gatherings of ten or fewer people for religious services, or for Memorial Day celebrations. This clearly favored two types of gatherings based upon the content of expression, and was therefore unconstitutional. New York was sued and subsequently modified its social gathering restrictions to allow groups of up to ten to gather for any lawful purpose or reason. Many of the “Black Lives Matter” protests seem to have violated restrictions on public gatherings. Did they receive preferential treatment? Perhaps. That will be the subject of the next blog post. I know that there was a lot of legalese to get through, but the issues presented are important. So, I have listed some of the important points to remember. Key Takeaways:

If you enjoy reading this type of commentary please subscribe to my blog and tell a friend. You will receive an email notification when new blogs are posted. The email will come from the site’s email: [email protected]. Thanks, Armchair American

0 Comments

|

AuthorThe Armchair American. Archives

June 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed